My spring classes have begun at the University of Massachusetts and I’ve been thinking a lot about my responsibility as an educator to help the graduating students in our program find good work.

My spring classes have begun at the University of Massachusetts and I’ve been thinking a lot about my responsibility as an educator to help the graduating students in our program find good work.

Our Sustainable Food and Farming major in the UMass Stockbridge School of Agriculture has grown significantly over the past 10 years (from just 5 students in 2003 to almost 100 today). While this doesn’t make it a large program at UMass, it makes it one of the largest sustainable agriculture programs in the U.S.

This dramatic increase in interest in sustainable food and farming education is being driven by “external” forces like the a growing local food culture coupled with a depressed national economy, as well as “internal” forces like the passion and commitment young people have to find real and meaningful work.

While most of my colleagues have celebrated this rapid growth in our program, a few have raise the concern that this many students may not be able to find well-paying jobs upon graduation. As their adviser, I take this concern seriously and try to point students toward good opportunities in the working world. Perhaps just as important however, I encourage them to reflect upon the difference between “finding a job” and pursing their “calling.”

Good Work

As Matthew Fox points out in his book “The Reinvention of Work“, there is a big difference between a “job” and “good work.” The great British economist, E.F. Schumacher (most famous for his 1973 landmark book Small is Beautiful), wrote a less-known book called Good Work about this topic. According to Schumacher, good work should...

As Matthew Fox points out in his book “The Reinvention of Work“, there is a big difference between a “job” and “good work.” The great British economist, E.F. Schumacher (most famous for his 1973 landmark book Small is Beautiful), wrote a less-known book called Good Work about this topic. According to Schumacher, good work should...

- …provide the worker with a living (food, clothing, housing)

- …enable the worker to perfect their natural gifts & abilities

- …allow the worker to serve and work with other people

A “job” can “provide a living (food, clothing, housing)” but good work is needed for us to be fully human. In an interview, Matthew Fox stated “a job is something we do to get a paycheck and pay our bills. Jobs are legitimate, at times, but work is why we are here in the universe. Work is something we feel called to do, it is that which speaks to our hearts in terms of joy and commitment.”

Those of us for whom our job is also our calling might celebrate Robert Frost’s words in Two Tramps in Mudtime:

My object in living is to unite

My avocation and my vocation

As my two eyes make one in sight.

How many us can claim that our avocation (that which we love) and our vocation (that which “pays the bills”) are truly as two eyes made one in sight?

Asking the Right Questions about Work

As important as finding a job is after college, it also seems to me that the emphasis on preparing students for a job results in an impoverished understanding of a college education. At a recent “majors fair” I was saddened by the number of students whose first question to me was “so how much money will I make when I graduate from this major?” Wrong question! While a job and salary are obviously important it should not be the first question a student asks about a potential career.

As important as finding a job is after college, it also seems to me that the emphasis on preparing students for a job results in an impoverished understanding of a college education. At a recent “majors fair” I was saddened by the number of students whose first question to me was “so how much money will I make when I graduate from this major?” Wrong question! While a job and salary are obviously important it should not be the first question a student asks about a potential career.

Matthew Fox reminds us that everyone of us has a calling and he explores several questions that may help us discover the reason we are here on this earth at this time. He asks us to consider these questions:

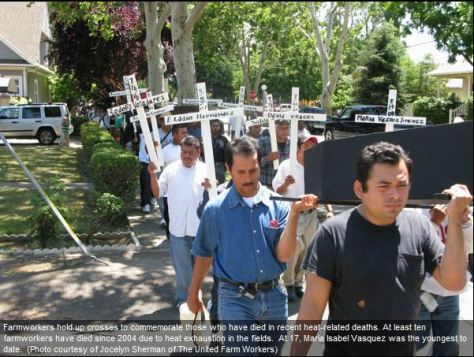

What are our talents? What is the pain in the world that speaks to us that we want to respond to? What gifts do we have, whether material goods or power to influence? What gifts do we have to make a difference? We are all living under this sword of the collapse of the ecosystem and what are we doing about it? Are we planting trees, are we working in the media to awaken consciousness, are we working to preserve the species that are disappearing or the soil or the forests? Are we cutting back on our addiction to meat, changing our eating habits, using less land, water and grain for our eating habits? Are we being responsible, and how does it come through in our work and in our job?

What are our talents? What is the pain in the world that speaks to us that we want to respond to? What gifts do we have, whether material goods or power to influence? What gifts do we have to make a difference? We are all living under this sword of the collapse of the ecosystem and what are we doing about it? Are we planting trees, are we working in the media to awaken consciousness, are we working to preserve the species that are disappearing or the soil or the forests? Are we cutting back on our addiction to meat, changing our eating habits, using less land, water and grain for our eating habits? Are we being responsible, and how does it come through in our work and in our job?

Of course, I can see some of my colleagues roll their eyes as they recite their job-focused mantra “yes, but it won’t matter if they can’t find a job!

Okay, so lets think about the jobs of the future? What will they look like? And what can we do to help prepare students for a job?

The Future of Work

The “smart” people tell us that the world is changing fast in response to advances in technology and continuing commoditization of work, resulting in an ever growing gulf between the “haves and the have-nots.” Futurist Ross Dawson reminds us that “…unless your skills are world-class, you are a commodity.” And the trend for the price of a commodity (including labor) is inexorably downward. Salaries of the highest wage earners continue to rise while those of the lowest continue to fall.

Among the industrial nations, the disparity between the salaries of upper management and workers is particularly onerous in the U.S. Even a college education may not be enough to provide a graduate with financial security in a society of growing inequity. Preparing students for an entry level job, without helping them also discover their calling and learn how to adjust and adapt to a rapidly changing world, simply prepares young people for being a commodity. We owe it to our students to do more than prepare them for being “cogs in a corporate machine.”

Among the industrial nations, the disparity between the salaries of upper management and workers is particularly onerous in the U.S. Even a college education may not be enough to provide a graduate with financial security in a society of growing inequity. Preparing students for an entry level job, without helping them also discover their calling and learn how to adjust and adapt to a rapidly changing world, simply prepares young people for being a commodity. We owe it to our students to do more than prepare them for being “cogs in a corporate machine.”

As depressing as this may sound, Dawson and other futurists project even more challenging times ahead. We need to ask ourselves, in these tenuous times how do university educators help prepare students to be successful in a new and largely unpredictable world?

A Few Suggestions

1. Well the first thing we need to do is to define success in more than financial terms. Living simply, being useful to others, being part of a healthy family and community MUST be valued as legitimate forms of success.

2. Next, students (and others) need clarify their personal calling (the confluence of a vocation and an avocation). If jobs are not secure, preparing for a job (even a well-paying job) that may exist today and be gone tomorrow is a bad plan.

3. Developing practical skills (like being able to fix a small engine, grow food, build a bike-carrier, graft a fruit tree, find relevant information on a smart phone or tablet, build a solar oven, or make a cup from clay), community-building skills (like knowing how to build coalitions of people who hold common values to work together), and system thinking skills (like knowing how to uncover root causes and shift the structure of complex systems), might be the most useful prerequisites for success in a rapidly changing world.

3. Developing practical skills (like being able to fix a small engine, grow food, build a bike-carrier, graft a fruit tree, find relevant information on a smart phone or tablet, build a solar oven, or make a cup from clay), community-building skills (like knowing how to build coalitions of people who hold common values to work together), and system thinking skills (like knowing how to uncover root causes and shift the structure of complex systems), might be the most useful prerequisites for success in a rapidly changing world.

4. Finally, everyone must learn to learn how to learn so they are ready to adapt to rapidly changing conditions. Too much of higher education is about remembering facts. Students graduate college with the dual skills of knowing how to take tests and how to write term papers, skills that are valued no where outside the university. Demonstrating they are “smart” (by getting good grades) is less important when many of the facts they have memorized for their exams are easily accessible on their smart phones. Blooms hierarchy of learning (below_ reminds us that “remembering” is the low end of learning.

Education for the future

Education for the future

The Sustainable Food and Farming major in the UMass Stockbridge School of Agriculture encourages students to explore experiential learning opportunities on farms, in markets and cooperative stores, non-profit advocacy organizations, and teaching situations while in college.

The Sustainable Food and Farming major in the UMass Stockbridge School of Agriculture encourages students to explore experiential learning opportunities on farms, in markets and cooperative stores, non-profit advocacy organizations, and teaching situations while in college.

In addition, there are many opportunities such as the UMass Real Food Challenge to earn college credit by working with other students to gain real-world experience while earning a Bachelor of Sciences degree in our program.

Education for the future needs to be less focused on memorizing facts and more on applying those facts to solve problems. Information is relevant but if necessary facts can be looked up on a smart phone, it is not worthy of higher education.

Education for the future needs to be more experiential, giving students the opportunity to “create, evaluate, and analyze” in real world situations. A university education should be a practice field where it is safe to “fail.” Students should be put into situations where they can learn how to learn how to learn so they are ready to adapt to a rapidly world.

Anything less is a failure of imagination.

ENDNOTE: I”m curious to learn about your own experience of higher education. Have you had the opportunity to “practice” in a real world situation while in college? Please share your stories in the comments box below.

===========================================================

See the Sustainable Food and Farming program at the University of Massachusetts for information on our Bachelor of Sciences degree.

Pope Francis declares global capitalism the “new tyranny”

Pope Francis declares global capitalism the “new tyranny” Inequality is not inevitable, but rather the result of economic institutions designed by Continue reading Catholic leader calls for an end to “business as usual”

Inequality is not inevitable, but rather the result of economic institutions designed by Continue reading Catholic leader calls for an end to “business as usual”