This post examines the structure of human-constructed hierarchy using a systems thinking lens. Like many of my friends who have a “problem with authority” – I always struggle with the concept of hierarchy. I think this is because the dominant form of hierarchy working in the human world is based on what peace and social justice activist Starhawk calls power-over and is manifested as domination (at best) and oppression or abuse (at worst).

POWER-OVER HIERARCHY – A HUMAN CONSTRUCT

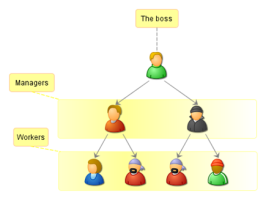

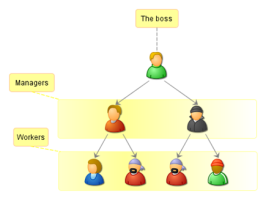

Power-over hierarchy is most apparent in the military, but is also found in corporations, universities, and many religious organizations (that is, just about every major human organization ever known). Power-over hierarchy, built upon “command and control” relationships is deeply rooted in human history.

Power-over hierarchy is most apparent in the military, but is also found in corporations, universities, and many religious organizations (that is, just about every major human organization ever known). Power-over hierarchy, built upon “command and control” relationships is deeply rooted in human history.

One of the early records of hierarchy is found in Exodus 18. When Jethro, the father-in-law of Moses, came to him “in the wilderness, where he was camped near the mountain of God,” he found Moses sitting all day making decisions over disputes among his people. He asked Moses “why do you sit alone as judge?” He advised Moses to “select capable men from all the people—men who fear God, trustworthy men who hate dishonest gain —and appoint them as officials over thousands, hundreds, fifties and tens.” There it is! One controls the 10, ten controls the 50, etc., etc….

Human hierarchy runs deep. This mode of decision making is the standard way humans have organized for thousands of years. It is so much part of our culture that it appears to be the ONLY way to understand hierarchy. While efficient in one sense, it is inherently unjust.

Human hierarchy runs deep. This mode of decision making is the standard way humans have organized for thousands of years. It is so much part of our culture that it appears to be the ONLY way to understand hierarchy. While efficient in one sense, it is inherently unjust.

But there is another way to think about hierarchy….

POWER-WITH HIERARCHY – NATURE’S WAY

While its true that humans have had thousands of years of experience organizing as power-over (command and control) hierarchies, ecological systems have several billion years of experience operating as power-with hierarchies. That is, rather than power being manifested as command and control (power-over), it is seen as participation and inclusion (power-with). Perhaps there is something we can learn from Mother Nature?

References to nature’s hierarchy are almost as old as the story of Exodus. The first time we find nature’s hierarchy in literature is associated with Aristotle and is called the Great Chain of Being, or scala naturae (literally the “ladder or stair-way of nature”). This ancient understanding of all relationships in the universe began to provide us with a sense of order and meaning. More recently modern systems thinkers have added to this model of the universe.

References to nature’s hierarchy are almost as old as the story of Exodus. The first time we find nature’s hierarchy in literature is associated with Aristotle and is called the Great Chain of Being, or scala naturae (literally the “ladder or stair-way of nature”). This ancient understanding of all relationships in the universe began to provide us with a sense of order and meaning. More recently modern systems thinkers have added to this model of the universe.

Today, we understand a natural hierarchy (or holarchy in systems jargon) as a nested set of “systems within systems” of increasing complexity. An organism (like you and me) contain “lower” or less complex subsystems like the human heart, and likewise are contained within the “larger” more complex subsystem of the human population. This is how living systems are organized and might depicted like this.

Now, what can we learn from this understanding of hierarchy? Well…… one of the most important lessons has to do with the relationship between the levels of complexity. A basic truth about natural hierarchies is “we look up for purpose and down for function.”

Now, what can we learn from this understanding of hierarchy? Well…… one of the most important lessons has to do with the relationship between the levels of complexity. A basic truth about natural hierarchies is “we look up for purpose and down for function.”

WHAT?

That’s right…. we look to more complex subsystems for purpose. For example, an individual cell finds purpose in serving an organ (like the heart). The purpose of the human heart, in turn, is to serve the human body (organism). And, the organism looks to the less complex subsystems for function. The organism looks to the heart for function. The heart looks to individual cells for function.

GET IT?

Well, if this makes sense to you we might then ask the question…. so what?

YIKES….. its a big “so what!” In fact it helps me to understand who I am and why I am here. If I am indeed “a part of nature rather than a part from nature” then my relationship with all that is living is clear. I too “look up for purpose” – that is, I am a “child of the universe” and my purpose is to be useful to something larger than myself. If we apply the principle of “look up for purpose” we might see ourselves as part of “larger” or more complex “selves.”

For example, I am certainly part of a “family-self” and a “community-self”, so why not think of myself as part of an “ecological-self”, “universal-self” or even a “divine-self”? This helps me to see that my purpose is to serve something larger than my personal self.

In a society when so many people seem to lack purpose (and therefore may substitute amusements or worse addictions for a meaningful life), the recognition that you and I are necessary to the function of more complex systems can be empowering. The system we serve may be our family, community, nation, Mother Earth, or perhaps a sense of the divine.

In a society when so many people seem to lack purpose (and therefore may substitute amusements or worse addictions for a meaningful life), the recognition that you and I are necessary to the function of more complex systems can be empowering. The system we serve may be our family, community, nation, Mother Earth, or perhaps a sense of the divine.

This understanding of hierarchy based on living systems theory, might allow us to organize more human endeavors based on power-with relationships. In this case, power comes from working with others at the same level of the hierarchy in service to a larger or more complex level. Working in local communities for example, we can take actions together that serve others in the nation or protect and nurture “Mother Nature” (the eco-self). Unlike the human hierarchy, the natural hierarchy is less likely to be unjust.

IMPLICATIONS

Power-over hierarchy it is NOT the only way of organizing human activities. Some businesses have learned that as they add layers of organization between top management and customers they lose access to feedback and begin to make poor decisions. Likewise political leaders lose touch with constituents when there are many layers of organizational hierarchy. This also explains why “conquerors” throughout human history rarely retain power for very long.

Power-over hierarchy it is NOT the only way of organizing human activities. Some businesses have learned that as they add layers of organization between top management and customers they lose access to feedback and begin to make poor decisions. Likewise political leaders lose touch with constituents when there are many layers of organizational hierarchy. This also explains why “conquerors” throughout human history rarely retain power for very long.

Conservationist, Aldo Leopold, reminded readers in his classic essay The Land Ethic, that conquest is always self-defeating, as conquerors rarely know “what makes the community clock tick, and just what and who is valuable… in community life.” Power-over conquest always fails, eventually. The “command and control” hierarchy that represents the dominant mental model governing how humans choose to organize has certain deficiencies.

Conservationist, Aldo Leopold, reminded readers in his classic essay The Land Ethic, that conquest is always self-defeating, as conquerors rarely know “what makes the community clock tick, and just what and who is valuable… in community life.” Power-over conquest always fails, eventually. The “command and control” hierarchy that represents the dominant mental model governing how humans choose to organize has certain deficiencies.

If you have to cross a desert with a “stiff-necked people” (Exodus 32:9), then perhaps a command and control hierarchy is needed. Or if you are fighting a war, then perhaps power-over is the relationship of choice. However if you are trying to create a sustainable society based on economic vitality, environmental quality AND social equity….. the human hierarchy just isn’t adequate. For example, (with apologies in advance to all of my fellow Roman Catholics who I may offend) I do not believe the Catholic Church will ever be fully successful sharing the message of peace, justice, forgiveness and love attributed to Jesus as long as it is organized as a command and control hierarchy. As I stated at the beginning, If power-over is the dominant relationship in an organization, it will ALWAYS result in domination (at best) and oppression or abuse (at worst).

If you have to cross a desert with a “stiff-necked people” (Exodus 32:9), then perhaps a command and control hierarchy is needed. Or if you are fighting a war, then perhaps power-over is the relationship of choice. However if you are trying to create a sustainable society based on economic vitality, environmental quality AND social equity….. the human hierarchy just isn’t adequate. For example, (with apologies in advance to all of my fellow Roman Catholics who I may offend) I do not believe the Catholic Church will ever be fully successful sharing the message of peace, justice, forgiveness and love attributed to Jesus as long as it is organized as a command and control hierarchy. As I stated at the beginning, If power-over is the dominant relationship in an organization, it will ALWAYS result in domination (at best) and oppression or abuse (at worst).

The only human examples I can think of that might at least partially model a natural hierarchy are the first century Christians and modern 12-step programs. Do you know of any human organizations based on power-with?

Perhaps after thousands of years of trying to get the power-over human hierarchy to work, it is time to give the much older power-with natural hierarchy a try!

==========================================================

I’d appreciate it if you would share this post with your friends. And for more ideas, videos and challenges along these lines, please join my Facebook Group; Just Food Now. Or for more systems thinking posts, try this link.

I’m gearing up to teach my favorite class again this fall at UMass,

I’m gearing up to teach my favorite class again this fall at UMass,