| “We Christians, in fact – British and American – were the ones who decided that we couldn’t do to Indigenous people and kidnapped Africans what we were doing if they were indeed people made in the image of God. What we did is we threw away Imago Dei. We threw it away to justify what we’re doing… white supremacy was America’s original sin… “ |

Many Unitarian Universalist congregations in the U.S. have voted to adopt the Eighth Principle which commits those congregations to “…actions that accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions.” American Unitarian Universalists like to point to our history as a liberal religion associated with the abolitionists in the early 19th century. At the same time, we need to be cautious about self-congratulatory rhetoric that ignores our historic complicity in the genocide, land theft and attempted erasure of Native peoples on this continent.

Acknowledging the contribution of our Calvinist religious ancestors to the genocide of Native peoples and the failure of Unitarians and Universalist ministers to speak out against the deportation of entire Native nations in the 19th century, might be a reasonable first step toward the work of repentance and repair that is long overdue.

Of course, the white supremacy culture that the Reverend Wallace refers to above as “America’s original sin” did not begin in the churches of colonial New England. The “just war theory” of 4th century bishop Augustine of Hippo and the “doctrine of discovery” promulgated by papal bulls of Pope Nicholas V in 1455 and Pope Alexander VI in 1493 laid the foundation for exploitation of native peoples by European settlers. Nevertheless, white supremacy and its associated violence were firmly planted on this continent at the Plymouth Plantation and the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early 17th century. And our religious ancestors were there at the time.

Roots of Unitarian Universalism in New England

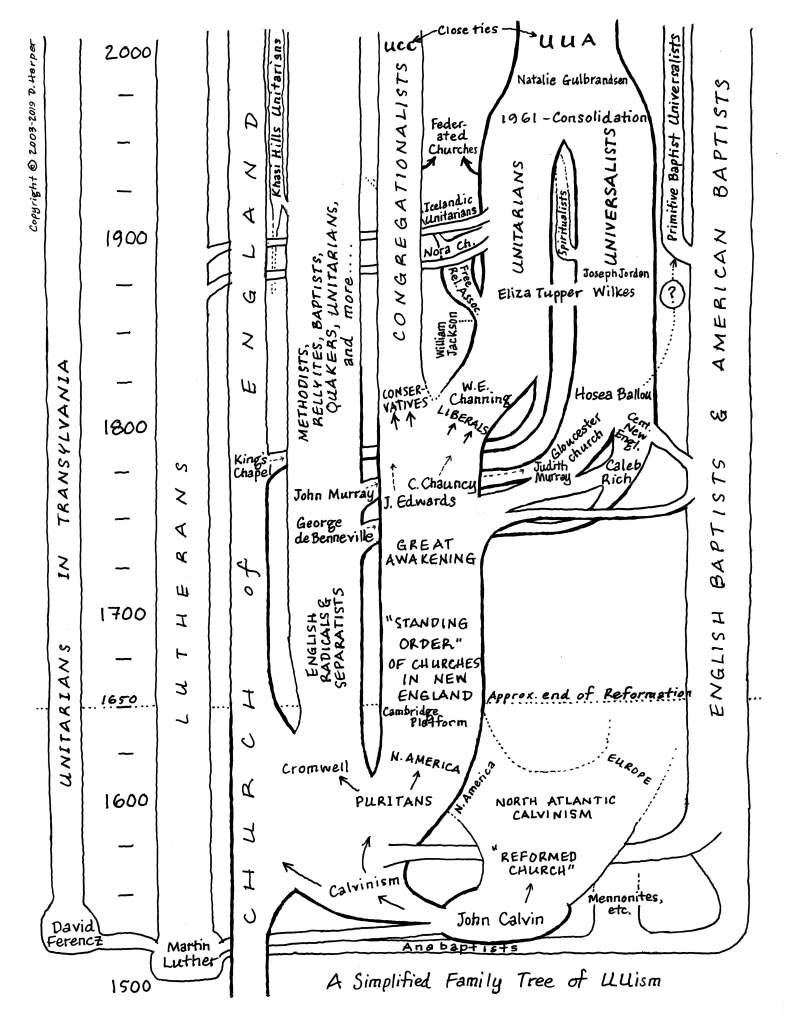

According to the Unitarian Universalist Association, the religious movement that evolved into both Unitarian and Universalist denominations in North America began with the Cambridge Platform of Church Discipline signed by English settlers in 1649.1 This platform described a system of church self-governance, free from hierarchical control, that continues to guide congregational churches of New England (including UU congregations) to this day. The Cambridge Platform affirms that the government should punish idolatry, blasphemy, heresy, and “the venting of corrupt and pernicious opinions”. This position gave the colonial government an endorsement from the Standing Order of New England Clergy (see diagram below) to punish indigenous people who were generally viewed as “corrupt and pernicious”

The image above is from “Family Tree for Unitarian Universalism“.

The congregationalist churches of New England were guided by a covenant that required devotion to God and mutual responsibility to other members of the church community. What was clear from the beginning however, was that Native peoples were not included within the covenant. Efforts to “save the Indians” during the 17th and 18th centuries were mixed with the violent removal of indigenous peoples from the land they had occupied for millennia. There was little trust between the Europeans and even the most compliant “Praying Indians” who were said to have experienced “a spiritual transformation from heathenism toward civilization that made them more like Englishmen.” The general narrative espoused from congregationalist pulpits during the 17th and 18th centuries presented Native peoples as “permanently barbaric and cut off from God’s salvation.” 2

One example was the Reverend John Eliot, pastor of the Roxbury, MA congregation, who was known as the “apostle to the Indians” for his genuine attempt to bring indigenous peoples into covenant with English settlers. According to American Indian scholar George Tinker, Eliot was blinded by his belief in the superiority of white culture and contributed to the systemic conquest and genocide of Native peoples as much as the vigilante groups of settler colonialists and the British military.3

The “Second Great Awakening” (1800-1840)

The emergence of a progressive theology and rejection of Calvinist orthodoxy was a gradual process resulting in the radical transformation of many of the congregationalist churches of New England. It might be assumed that a faith that came to espouse the “inherent worth and dignity of all persons” would recognize its complicity in the harms done to Native peoples. Several leading Unitarian and Universalist speakers alluded to these harms and might have led efforts at repentance but mostly remained silent.

Unitarian educator Horace Mann (1796-1859) for example advocated for universal public education and included Native Americans among those in need of becoming part of the mainstream of white society.

Unitarian minister Samuel J. May (1797-1871) spoke in favor of humane treatment of enslaved as well as Native peoples, who needed to be taught Western norms of behavior.

Thomas Starr King (1824-1864) expressed sympathy for the impact of the California gold rush on Native Americans currently occupying the land being mined by white adventurers.

Universalist minister Caroline Soule (1824-1903) expressed genuine concern for Native welfare but espoused an assimilationist solution.

James Freeman Clarke (1810-1888) promoted the idea of universal brotherhood and declared that Native Americans were in need of guidance and should be “wards” of the nation.

The common theme among the most progressive Unitarian and Universalist speakers of the 19th century was that Native peoples were in need of salvation which could be achieved by adopting white European ways of living. Explorations of the written record produced no clear outcry by Unitarian or Universalist ministers against the abuse of Native Americans. This is especially concerning as most of these ministers and writers lived during the time of the forced displacement of about 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole nations from the American southeast.

The Deep Roots of White Supremacy

The deep roots that our religious ancestors had into the project of erasure and oppression of Native Peoples was thoroughly documented in 1936 by the Reverend Samuel A. Eliot II, president of the American Universalist Association. Speaking to the Commonwealth Club of San Francisco, Reverend Eliot told the story of the “of the oldest missionary society of American origin”, the Society for Propagating the Gospel among the Indians and Others in North America.4

This Society was established in 1787 by twenty-one well-regarded leaders and active members of the Boston church community. According to Eliot “…they were, intellectually and politically and ecclesiastically, of the same type. Most of them were Harvard graduates of the thirty years between I747 and 1777. Of this group, four ministers were the prime movers in the organization of the Society.4

The Reverend Samuel A. Eliot suggested that the relationship between Native peoples and the dominant white society had gone through various stages over the years from an attitude that Indians were dangerous, to becoming a problem, and later to being a mere nuisance. Eliot wrote that the people of his own day (the 1930’s) came to realize that they had “…some responsibility for these primitive people.” And further that a “…practical and vocational school program must fit him to take his part in the industrial and social life of the community.” 4 Toward this end, the American Unitarian Association supported Indian boarding schools in Montana, Minnesota, and Colorado that forcefully assimilated nearly 4,000 indigenous children. From the efforts of John Eliot to “civilize the Indian” in the 17th century to the establishment of the boarding schools in the19th and 20th centuries, the overall impact of our religious ancestors’ work was harmful.

Repentance Begins by Acknowledging the Harms Done

UU Minister, the Reverend Jill Cowie, in a November 2017 sermon, stated that “the intellectual, moral, and spiritual justification for European colonization and slavery” was rooted in the teachings of the Christian church and were “…used by our Protestant ancestors of the Mass Bay Colony and the Virginia colony to justify the subjugation of indigenous people in this country… a conquest that led to multiple broken treaties, the trail of tears, the formation of over 300 reservations, mandatory boarding schools, cultural obliteration, and genocide.”5

UU’s nationwide participated in a Common Read of the book, “Repentance and Repair, Making Amends in an Unapologetic World” by Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, during 2023. The first step in repentance and repair according to Rabbi Ruttenberg is to “name and own” the harm that was done. Toward this end, delegates at the 2020 General Assembly6 of the UUA6 boldly stated that:

“…the Pilgrims’ invasion of the Wampanoag people led to the enslavement of Indigenous peoples on the East Coast and the removal of and genocide against Indigenous peoples across the continent.

“… many Unitarian Universalist congregations uncritically trace their origins to the Pilgrims’ “Free Church” tradition – a mythos that sanctifies white supremacy and depends upon erasure of Indigenous peoples. “

The next step, even before any apology and repair work begins, is to “start to change and stop causing harm.” According to the UUA, the white supremacy culture that was deeply embedded in the churches of our ancestors7 remains a powerful force “hidden in plain sight” in some Unitarian and Universalist congregations today.8 All of our UU meetinghouses reside on stolen land. It is unlikely that we will “accountably dismantle racism and other oppressions in ourselves and our institutions” as it states in our own Eighth Principle, until we do the necessary repentance and repair work associated with America’s original sin.

This topic is continued in the next blog post….. Repentance and Repair (continued) here: https://changingthestory.net/2024/02/02/repentance-continued/

References

- UUA Webpage – Values in our History.

- Michna, Gregory. Puritan Sermons and Ministerial Writings on Indians During King Philip’s War. Sermon Studies 1.1 (2017): 24-43.

- Tinker, G. Missionary Conquest: The Gospel and Native American Cultural Genocide. Fortress Press. 1993.

- Eliot, Samuel A. A Sketch of the Origins and Work of an Old Massachusetts Society. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, Third Series, Vol. 66 (Oct.,1936 – May, 1941), pp. 107-125

- Cowie, J. Decolonizing Our Faith (a sermon from November 2017) –

- UUA Webpage. Address 400 Years of White Supremacist Colonialism- Action of Immediate Witness. 2020

- Cerrotti, D. Hidden Genocide: Hidden People. Sea Venture Press. 2014.

- Hewitt, E. & H. de la Fuente, J. Dismantling White Supremacy Culture in Worship. 2021

Additional Resources

Research into the Harms Done by UUSA Religious Ancestors

A Statement on the Current Status of Native Peoples from Food First

400 Years: Truth & Healing for he Next Seven Generations

Examples of repentance and repair work by UU congregations

————————————————————

6 thoughts on “Repentance for “America’s Original Sin””