Last week’s blog focused on one of the three big problems of our time, Peak Oil. This week we are looking at the threat of Global Pandemic caused at least partially by industrial animal agriculture (factory farms). According to the Director General of the World Health Organization, the three major problems of our time are:

- Peak Oil

- Global Pandemic

- Climate Change

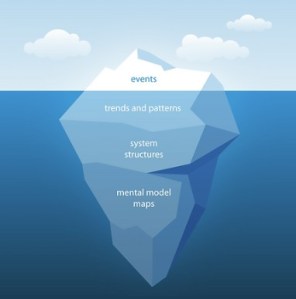

There is evidence that the bird flu and swine flu epidemics of the past few years originated in factory-farms in Southeast Asia and Mexico. The industrial response to bird flu was typical of modern culture – proposals to irradiate meat, flu vaccines for the birds, efforts to outlaw backyard chickens. The real problem is the system we have created to make sure our meat products are cheap – factory farms (these are “structures” in our iceberg tool that we use to understand root causes). Perhaps an even more immediate concern however, is the potential loss of antibiotics for human health care due to their extensive use in factory farms. If you WANTED to create antibiotic resistant bacteria, this is how to do it:

- Inoculate a petri dish with bacteria, which will grow like crazy

- Apply an antibiotic, which will probably kill 99% of the bacteria

- Feed the surviving 1% with sugar water, and it will “grow like crazy”

- Apply an antibiotic to the new growth, which will probably kill 99%

- Again feed the surviving 1% sugar water, and it will……

Do this again and again and again…. and what you end up with is a strain of bacteria that is resistant to antibiotics! And this happens BY DESIGN in at least two places in modern culture….

In a Johns Hopkins magazine article from June 2009….. Kellogg Schwab, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Water and Health, spoke about samples he collected from a lagoon used to store pig manure. “There were 10 million E. coli per liter [of sampled waste]. Ten million! And you have a hundred million liters in some of those pits. So you can have trillions of bacteria present, of which 89 percent are resistant to drugs. That’s a massive amount that in a rain event can contaminate the environment.”

He adds….

“This development of drug resistance scares the hell out of me. If we continue on and we lose the ability to fight these microorganisms, a robust, healthy individual has a chance of dying, where before we would be able to prevent that death.“

Schwab says that if he tried, he could not build a better incubator of resistant pathogens than a factory farm.

This is crazy!

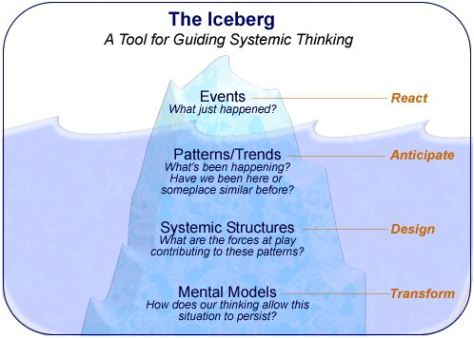

Lets use the iceberg tool again to try to answer the question “why do we do this to ourselves?“.

So, once again I asked my class…. “what is the root cause of this crazy human behavior?”

So, once again I asked my class…. “what is the root cause of this crazy human behavior?”

In this case, an event might be a single hog or chicken that was treated with a low level dose of antibiotic to help it grow faster.

A pattern would be thousands of chickens treated with antibiotics to keep them alive while living in a crowded, unhealthy environment.

The more interesting questions are about the structures and mental models that make these crazy behaviors “normal.”

Among the structures named were:

- Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (factory farms)

- pharmaceutical industry

- government regulation

- advertising industry

- fast food industry

- what else?

And the mental models that make these structures “normal” might be:

- a belief that everyone needs animal protein daily

- the expectation that food should be cheap

- the belief that animals are simply “units” not living beings

- the worldview that humans are not part of “mother nature”

- the hope that “government will protect us”

- “what other beliefs support this behavior”?

To change the patterns, we must change the structures used to raise animals. But to change the structures, we must change the way we think (mental models). Take a few minutes to compare these two systems for raising chickens, and look for the mental models under each of these structures:

2. My backyard

The local farm or backyard option is a real possibility, but to change these structures we must first change the way we think. And to change the way we think, we need to change the way we ourselves choose to live! The following is a short video comparing the way we treat animals with the way we live our lives…..(can you see shared mental models?).

…………

To change the way we treat animals, we need to change the way we live our lives. What are you doing to change your own life!

====================================

So a student shows up in my office asking

So a student shows up in my office asking