One of my previous posts described how the modern industrial food system is in “collapse.” In this post, I offer some ideas on how town government, local colleges and community organizations can get involved to .…

“just grow food – and – grow food justly.”

While the USDA, the American Farm Bureau and national commodity groups like to talk about promoting local agriculture, most of their policies are more supportive of “big agriculture.” If we are going to “grow food justly” we might want to look closer to home. We need to start in our own backyards and neighborhoods and then work with town government, colleges and community organizations to strengthen the local food system.

This blog focuses on my experience working in my hometown, Amherst, Massachusetts.

Local Opportunities

One of the mantras from “big ag” is that you can’t feed the world with local food. Well lets think again. First, we need to ask what do we mean by local? For a New Englander the answer may be obvious, as there is a strong sense of regional identity that stops at the Hudson River. One of my favorite stories is of an 18th century tax collector from New York who tried to impose his authority over independent Vermonters. Ethan Allen (of Green Mountain Boys fame) is reported to have shot him with buckshot (not fatally) and chased him away with the cry “…the gods of the valley are not the gods of the hills.” Although today we clearly need to trade with those outside of our region, it would be good to know just how much food are able to grow for ourselves in New England.

Toward that end, the Amherst Agricultural and Conservation Commissions invited Dr. Brian Donahue, Professor of Environmental History at Brandeis University (and a local farmer himself), to speak to a group of local residents about what might be possible. Professor Donahue shared his estimates of how much food could be realistically produced in New England. He thought we could grow:

- Almost all of our vegetables

- Half of our fruit

- All of our dairy products

- Most of our beef and lamb

- Most of our pastured pork, poultry and eggs

The following 25-minute video clip from his presentation provides more detail:

Can we grow more food in New England?

Professor Donahue said that although this was possible, it was by no means going to be easy. If we want to grow more of our own food in New England, we have some work to do!

Local Responsibility

Ben Hewett’s book “The Town that Food Saved” tells the story of Hardwick, Vermont, a community that took responsibility for its own future. While Amherst, MA may be a more cosmopolitan community, local food has an important place in our history and culture as well. Our town emblem for example, is “the book and the plow”. These symbols represent our respective commitment to higher education (we have 3 colleges in town) and farming (we are proud of our agricultural roots). While this partnership is tested from time to time (as UMass faculty sometimes deride our history as a “cow college,” and farmers at times may laugh among themselves about the “eggheads” on campus), our success as a healthy community depends on mutual respect for both of these traditions. This partnership is one of the strengths of our town and a foundation upon which we are trying to build a vibrant community-based food system.

To build a more vibrant local food system, town government, the colleges and community organizations need to take more responsibility.

Here are a few ideas to consider, based on a few of our experiences in Amherst:

Local government might:

- pass a right to farm bylaw that protects farms and farmers from nuisance complaints,

- help private citizens purchase farm land for “ag value” while government purchases the development rights,

- change the zoning regulations to support the “homegrown food revolution” and allow chickens in backyards,

- provide access to public lands to support local farms, and

- pass a local bylaw providing an incentive for public bodies to buy local.

Colleges and universities can help by:

- developing their own working farms on campus,

- offering education programs encouraging family, neighborhood, community self-sufficiency, and local farming,

- providing real world farming experiences as part of the curriculum, and

- renewing their commitment to serving the public good.

Community organizations might:

- purchase land threatened by development to hold in trust and rent to farmers,

- create their own educational programs and become active in their community,

- raise private funds to purchase and preserve farm land and open space, and

- engage citizens as donors and members.

As an example of a community-led project, a study commissioned by our neighboring town, Feed Northampton, proposes a public investment in food hubs that might provide communal food processing, packaging, cold storage and redistribution. It might also include a slaughter facility, a community kitchen for processing vegetables, a maple sugar boiler, a cider press, and a flour mill. And residents of Sedgwick, Maine recently voted to adopt a Local Food and Self-Governance Ordinance, setting a precedent for other towns looking to preserve small-scale farming and food processing. If we are going to have a more robust local agriculture, we need to take more responsibility for creating that vision ourselves.

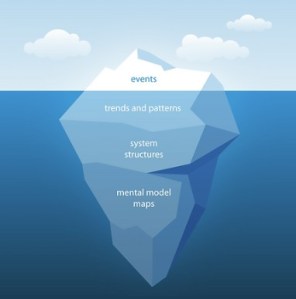

I believe that we must work together to build more resilience into a food system that is dominated by global corporations, vulnerable to collapse in the industrial world, and already in collapse in many developing countries (as evidenced by recent unrest) by growing more food locally.

However if your own town government, local organizations and colleges fail to provide leadership, it is up to “average” citizens to lead the way. If we “start parade” the local leaders will gladly jump up in front and wave our “local foods” flag! My next blog will examine personal responsibility for helping to create a vibrant community-based food system and ask the question, “so how do I help?”

==========================================================================

For more ideas, videos and challenges along these lines, please join my Facebook Group; Just Food Now. And for those of you from Amherst, please send me your favorite public initiatives to promote local food to add to my list for a future blog.