Did you know that 2012 is the United Nations International Year of the Cooperative?

Did you know that 2012 is the United Nations International Year of the Cooperative?

Well, students in the UMass Sustainable Food and Farming program and many people living in Western Massachusetts sure do! There have been lots of activities, events, and work in my neck of the woods related to the U.N. IYC.

Here are a few….

1. Rebekah Hanlon, former UMass student and currently a co-owner of Valley Green Feast spoke to the UMass Sustainable Living class on cooperatively managed businesses. Check out this short video on “why I prefer to work in a cooperative/collective business“.

2. The students in my UMass Writing for Sustainability class this spring sponsored a celebratory event in which over 100 students and faculty came to hear presentations by local food cooperatives in the region. Presenting at the celebration were:

2. The students in my UMass Writing for Sustainability class this spring sponsored a celebratory event in which over 100 students and faculty came to hear presentations by local food cooperatives in the region. Presenting at the celebration were:

- Equal Exchange – offering fair trade products from small farmers

- Earthfoods Cafe – a vegetarian cafe on the UMass campus organized as a collective since 1976

- Pedal People – a worker-owned human-powered delivery and hauling service for the Northampton, Massachusetts area

- Franklyn Community Cooperative – two local stores stores offering fresh organic produce, bulk foods, organic meats and cheeses and natural groceries and wellness items

- Valley Green Feast – offering fresh, organic and local food products delivered to your home or workplace

Adam Trott, from the Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives was the keynote speaker.

3. In recognition of the extraordinary efforts of the worker-owners of Valley Green Feast, our local newspaper did a front page story and a follow-up editorial praising their work. Here is an excerpt from the editorial:

3. In recognition of the extraordinary efforts of the worker-owners of Valley Green Feast, our local newspaper did a front page story and a follow-up editorial praising their work. Here is an excerpt from the editorial:

This mission-driven business, run by four women, started five years ago as a food delivery service for people who might be customers for community-supported agriculture operations. This crew now says it is ferrying fresh, locally produced food to 300 households in the Valley and south into Connecticut. But this year it is also shaving its prices by 20 percent for low-income buyers and making do with those lower payments.

Though we live in a nation obsessed with appearances and worried about rising obesity, little headway is being made to help people shift from highly processed foods, which often contribute to weight gain, from nameless factories hundreds of miles away to healthier local alternatives. The four co-owners of Valley Green Feast are doing something about that by making fresh produce and other local farm products available at lower cost to people who qualify for benefits through the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

4. The University of Massachusetts Department of Economics recently launched a new certificate program in Applied Economic Research on Cooperative Enterprises. This program provides undergraduates with new opportunities for practical, field-based research while also promoting local economic development. Working in collaboration with the Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives (VAWC), UMass offers a course of study and internship combined with intensive, supervised summer research in this new program. This program is sponsored by the UMass Cooperative Enterprise Collaborative.

4. The University of Massachusetts Department of Economics recently launched a new certificate program in Applied Economic Research on Cooperative Enterprises. This program provides undergraduates with new opportunities for practical, field-based research while also promoting local economic development. Working in collaboration with the Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives (VAWC), UMass offers a course of study and internship combined with intensive, supervised summer research in this new program. This program is sponsored by the UMass Cooperative Enterprise Collaborative.

5. Graduating UMass student Nora Murphy, presented an idea for a local worker-consumer owned food cooperative designed to increase food access, provide meaningful employment and strengthen the local food system and economy, at the 2012 IGNITE UMass event. There is lots of interest in the new proposed Amherst Community Market.

5. Graduating UMass student Nora Murphy, presented an idea for a local worker-consumer owned food cooperative designed to increase food access, provide meaningful employment and strengthen the local food system and economy, at the 2012 IGNITE UMass event. There is lots of interest in the new proposed Amherst Community Market.

6. Finally, a small group of citizens associated with Transition Amherst is working to create a cooperatively managed store to be called All Things Local. The core idea is to create a resilient local community market by employing a model with lower costs (because of significant contributions from volunteers who care about the mission) and shared-risk (items are sold on consignment, rather than taking on debt to stock inventory).

- Convenient location and hours

- Year-round and indoors

- Ability to pick-and-choose among many local producers

- Single checkout, with all the usual payment options

- Producers set their own price

- 90% of the selling price goes back to the producer where it belongs

- Fast drop off

- Don’t have to be onsite (lower staffing costs)

- Online pre-sale bulk orders

Local producers, consumer advocates and organizers are working together to figure out how this concept might work. To follow our progress, see: All Things Local blog.

—————————————————

According to the U.N. IYC…

According to the U.N. IYC…

- Cooperative enterprises build a better world.

- Cooperative enterprises are member owned, member serving and member driven

- Cooperatives empower people

- Cooperatives improve livelihoods and strengthen the economy

- Cooperatives enable sustainable development

- Cooperatives promote rural development

- Cooperatives balance both social and economic demands

- Cooperatives promote democratic principles

- Cooperatives and gender: a pathway out of poverty

- Cooperatives: a sustainable business model for youth

We are celebrating the International Year of the Cooperative in Western Massachusetts. Tell us about what is happening in your region in the comments box below.

=====================================================================================

Please share this post with your friends. And for more ideas, videos and challenges along these lines, please join my Facebook Group; Just Food Now. And go here for more of my World.edu posts.

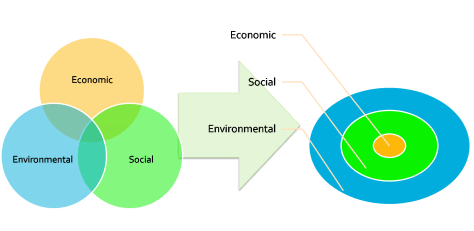

Almost everyone accepts some version of the “sustainability triangle” which includes 3 “E’s”…

Almost everyone accepts some version of the “sustainability triangle” which includes 3 “E’s”…